Man returns to childhood home against the odds

Saroo Brierley is a 36-year-old man with a powerful story of loss and love. As a 5-year-old child in India, he became impossibly lost in Calcutta, a sprawling, chaotic city of 14 million people. He said he had no money, no one to help him, no clue how to get back home. That he survived is amazing enough. What happened next got Hollywood's attention. His story is now a movie, called "Lion," the English translation of his Indian name. But there would be no movie, no story without Saroo's memories, the recollections of a terrified little boy. It's hard to recall events from age 5, but witnesses we talked to and documents we found support almost all that he remembers. As we reported last December, Saroo Brierley considers himself lucky to be alive. When you hear his story, we think you'll understand why.

Bill Whitaker: Tell me about the night you got lost. What do you remember?

Saroo Brierley: I remember it so vividly. It's-- it's a memory that's been within me for such a long time.

It began when Saroo Brierley was five in his village in central India. He lived in a cramped one room house made of cow dung and brick with his mother, two older brothers, and younger sister. His father had abandoned them leaving them penniless.

Bill Whitaker: Do you remember being hungry?

Saroo Brierley: We're always hungry. We were always sort of having to sort of live a day at a time.

Bill Whitaker: You found more food at the train station than anyplace else?

Saroo Brierley: If I really wanted to sort of find food, the train station is the best place. It wasn't just myself, there was other beggars and people at the train station too.

Bill Whitaker: Is that what you and your brothers were?

Saroo Brierley: We were beggars, yeah.

He says his mother would often leave the children for days on their own so she could earn less than a dollar a day hauling rocks at construction sites.

Saroo Brierley: When I saw her eyes as a child I know she was going through hardship.

Bill Whitaker: You remember thinking that, looking at your mother?

Saroo Brierley: Yeah. I'd see whilst I'm sort of sleeping or almost asleep next to my sister and I could see sort of tears going down her eyes as well.

One night, Guddu, his oldest brother he idolized, wanted to scavenge at the big train station down the track. Saroo says he begged to go with him. Reluctantly, his brother gave in. Saroo remembers the station had a water tower and a pedestrian walkway. He also remembers he was exhausted. When they got there, it was late at night.

Saroo Brierley: And I just wanted to go to sleep. And my brother said, "Wait here. I'll be back." I ended up going to sleep on the bench. I'm not too sure whether it was like 10 minutes, 20 minutes, an hour, two hours, three hours.

When he woke up, he remembers a train was there but his brother was not. Saroo thought he might be inside looking under seats for coins and food. He didn't find him but he did find a comfortable seat and fell back to sleep. When he woke up again, as depicted in the movie, the train was careening across India for hours and hours.

Saroo Brierley: It's a ghost train. No one's on the train. And--

Bill Whitaker: And the train is hurtling down the tracks--

Saroo Brierley: It's hurtling down the tracks. And I just ran up and down. Tears. I was locked in the carriage. I couldn't open it. I'm on this carriage, on this train, all by myself locked as a prisoner. Its prisoner.

Bill Whitaker: And you're five years old.

Saroo Brierley: And I'm five years old.

He thinks he was trapped more than a day. He ended up a thousand miles from home in the crowds and chaos of the main Calcutta train station. More than a million people pass through here every day.

Saroo Brierley: I was panicking. My heart was going triple time. I'm calling out for my brother, my sister and my mother.

Bill Whitaker: Was no one paying attention to a little-- little kid in the crowd?

Saroo Brierley: No one was paying attention. No. To them it's like you're just another kid outside the train station. You know? A beggar out from the train station.

To make matters worse: He spoke Hindi. In Calcutta, people speak Bengali. He avoided the police because, at home, police arrested beggars. So he'd have to do what he'd learned from his brothers. Survive on his wits and scavenge in a vast, unforgiving city threatening to swallow him up. He slept alongside other street kids in the train station but there were adult predators at night.

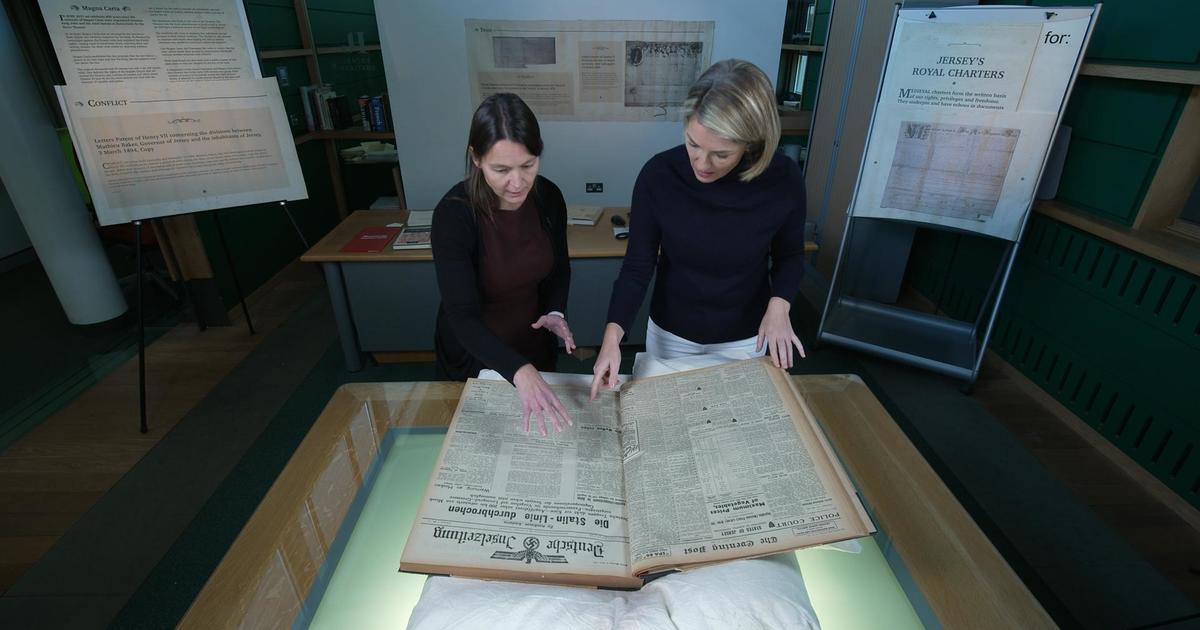

Saroo says he barely survived perhaps for weeks before a young man helped him and brought him to the police. A judge sent him to an orphanage. While the movie heightened the action for dramatic effect, we confirmed with the director of the orphanage that Saroo told his story of being lost when they took him in. The social workers wrote his story in this log.

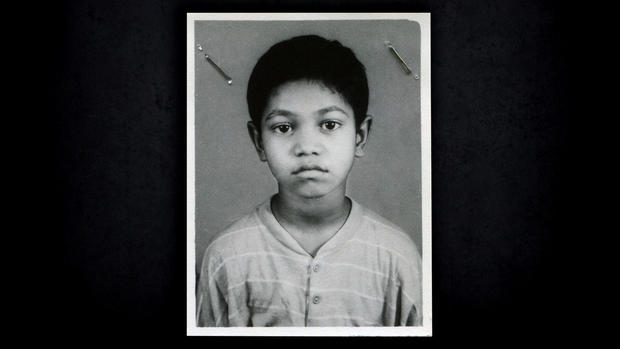

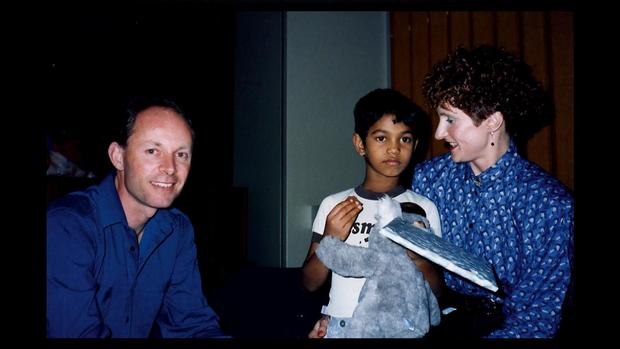

Five-year-old Saroo didn't know his last name, didn't know his address, didn't know the name of his village. They put his picture on flyers, on TV, in the paper. But no one responded. He was declared a lost child of India. The woman who ran the orphanage told Saroo a family in Australia wanted to adopt him. About six months after getting on that train, he got on a jumbo jet to Australia where he met his new mom and dad, Sue and John Brierley.

Bill Whitaker: What was that like when he gets off the plane?

Sue Brierley: (sigh) Oh.

John Brierley: Pretty incredible--

Sue Brierley: Yes.

John Brierley: Yeah--

Sue Brierley: It was just so amazing. He just had these incredible eyes. And calmness about him. He seemed a little bit cautious. But he didn't seem fearful.

They took Saroo back to their home on the Australian island of Tasmania where he had a toy filled room as big as his house in India. His new mother put a map of India on his wall so he'd always remember where he came from.

Sue Brierley: He virtually put his life in our hands from the first moment we met.

Bill Whitaker: You could feel that.

Sue Brierley: Yes. Yes. Definitely.

Bill Whitaker: They saved you.

Saroo Brierley: They did. But they didn't know my past and what had been. And I only told 'em to the point of you know as much language as I had that I could describe things.

Slowly, as he learned English in school, he began to reveal his past. He remembered details of the station where he got on the train to Calcutta. The water tower. The pedestrian bridge. He remembered the dam where he would play in the river. Sue wrote it all down in this diary. Under the love and care of Sue and John, Saroo thrived. He excelled at sports. He was popular at school.

Saroo Brierley: I was happy, I was comfortable, getting the love that I—that I've always sort of wanted.

Bill Whitaker: With your new life, did you think about your old life often?

Saroo Brierley: Of course I did. Those memories came alive when I went to sleep.

But sometimes in his waking hours, he would search the map of India hoping to recognize something, hoping to find his mother. He said he feared she was anguished over losing him.

Bill Whitaker: How did you feel about that?

Saroo Brierley: Helpless. That's what it was, at the end of the day. You couldn't do anything. You think about it quite a bit. I was holding onto those memories, never to let go.

Nearly 20 years after he went missing, he discovered he could use his memories like a mental map to find his way home. His discovery? Google Earth.

Saroo Brierley: It's just so massive. And this is what I've been sort of looking at.

With Google Earth, he could get a bird's eye view of towns and landmarks. He calculated a search radius from Calcutta based on the speed of trains and the time he thought he was locked on board. Night after night, he would follow the tracks looking for anything that would match his memory of the station where he got lost.

Bill Whitaker: So out of all of India, all the train stations in all of India, you're looking for a water tower and a walkway over the train tracks?

Saroo Brierley: Uh-huh (affirm). Basically, a needle in a haystack.

One night, frustrated by hours, years, of fruitless searching, he looked out farther than he ever imagined he could have traveled.

Saroo Brierley: All of a sudden I come to this train station here and I zoom down. It matched absolutely perfectly.

Bill Whitaker: The water tower's right there-

Saroo Brierley: The water tower is right there.

Bill Whitaker: And the pedestrian walkway.

Saroo Brierley: The flyover bridge, the pedestrian walkway.

Farther on, he saw the dam where he played in the river. It all matched what he'd told his adoptive mother Sue years earlier, down to the map they had drawn in the diary.

Bill Whitaker: Many people don't remember younger than five, but yet you remember in such great detail. Why do you think that is?

Saroo Brierley: I reckon what it is, is that I never went to school. So language wasn't really in me, you know. It was all visual. My visual senses were extremely heightened.

He knew he had to go to India to try to find his mother. At the airport, Sue gave him this photo. It's how he would have looked when his birth mother last saw him.

Saroo Brierley: And all of a sudden you know my emotions and everything just take over me, and I'm just in tears. It was almost like feeling, you know, before actually knowing, "Mum, I'm coming home to see you."

After 25 years, 16 hours on the plane, and a four-hour drive, he was finally home. It was just as he'd remembered – the path he'd walked many times to his house. But when he got there, it was abandoned.

Bill Whitaker: Your family's not there. What are you thinking?

Saroo Brierley: I thought "They're dead." I thought the worst. All the worst things that you could think of possibly was just going through my head.

Saroo, now an Aussie, stood out in the slum. He couldn't communicate. A man approached who spoke English. Saroo said he was looking for the family that had lived in this house. The man told Saroo to come with him.

Saroo Brierley: And I walked for about 15 meters just around the corner, and the man goes, "This is your mother." And she walked forward, and I walked towards her. We-- we're-- our eyes were locked together.

Bill Whitaker: What'd you see in your birth mother's eyes when you look in them for the first time in years?

Saroo Brierley: The tears that I saw when I used to look at her and I can see that she's struggling but this time it was tears of joy.

We sent our cameras to his home village. His mother Kamla told us "When I saw him I knew he was my Saroo." He's now been back to India 15 times. He reunited with his sister and one brother who both had moved to a nearby city. But his mother never left their village.

The movie shows the love between Saroo and his oldest brother Guddu, who took him to that train platform 25 years before. Kamla told Saroo his brother was killed on the tracks the very night Saroo was lost.

Bill Whitaker: On that one night your mother lost two sons?

Saroo Brierley: Yes and I can't think you know what she went through. It's like one is just you know here it is he's died but the other one he's just disappeared.

Bill Whitaker: Why did your birth mother decide to stay there in that very village?

Saroo Brierley: Because she felt that one day the son that she had lost would come back. And it was amazing because here I am, determined to find my hometown and my family from one side of the world, oceans apart, and here's my birth mother sitting there and waiting because she knew that one day her son would come back. And I'm so glad that she did.

Saroo is now helping his biological mother in India financially. But he considers Sue and John Brierley his mom and dad, and Australia his home.

Produced by Marc Lieberman. Michael Kaplan, associate producer.